Tsunami

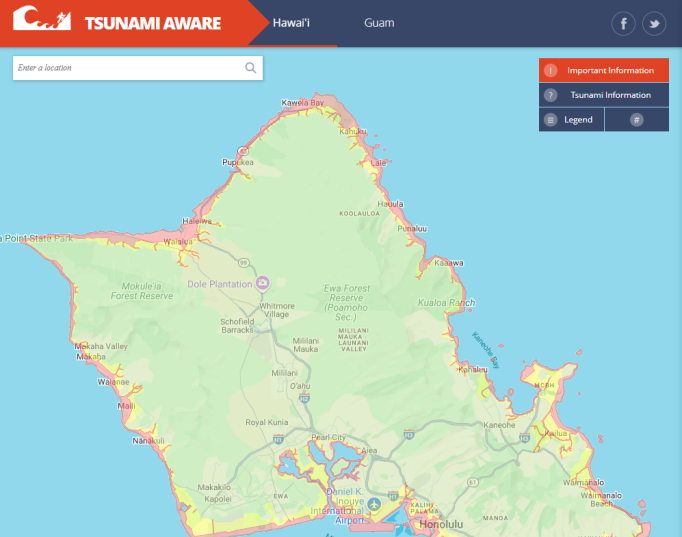

Note: To access Tsunami Evacuation Zone maps, click here.

What is a Tsunami?

A tsunami is a series of powerful waves usually caused by large earthquakes that displace the seafloor. These waves can travel thousands of miles across the ocean, at speeds over 500 miles per hour. Tsunamis are some of the most destructive and dangerous natural disasters. One of the deadliest natural disasters in recent history was the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004, which killed 227,000 people in Southeast Asia and Africa, and was caused by a 9.2-magnitude earthquake in Indonesia.

When tsunami waves approach shores, where water is shallower than the open ocean, the traveling waves slow down and build in height. Most tsunami waves are less than 10 feet high, but extreme tsunamis have produced waves over 100 feet high.

Hazards of tsunamis that threaten life and property include:

- Wave impacts along coastlines

- Flooding of low-lying coastal areas and inland waterways

- Strong currents that can last for days in some cases – Dangerous debris carried by floodwaters

Tsunamis cannot be predicted because they are caused by irregular geological events (usually earthquakes, but also landslides and volcanic activity). However, once a tsunami is generated, scientists have tools that can help forecast where and when the tsunami waves may impact land, how high the waves may be, and how long tsunami waves will last.

Sometimes, if a tsunami originates close to a coast – called a local tsunami – there is not enough time for officials to send detailed tsunami forecast information to people in the tsunami’s path. Therefore, it is important that you be able to identify the natural warning signs of a tsunami.

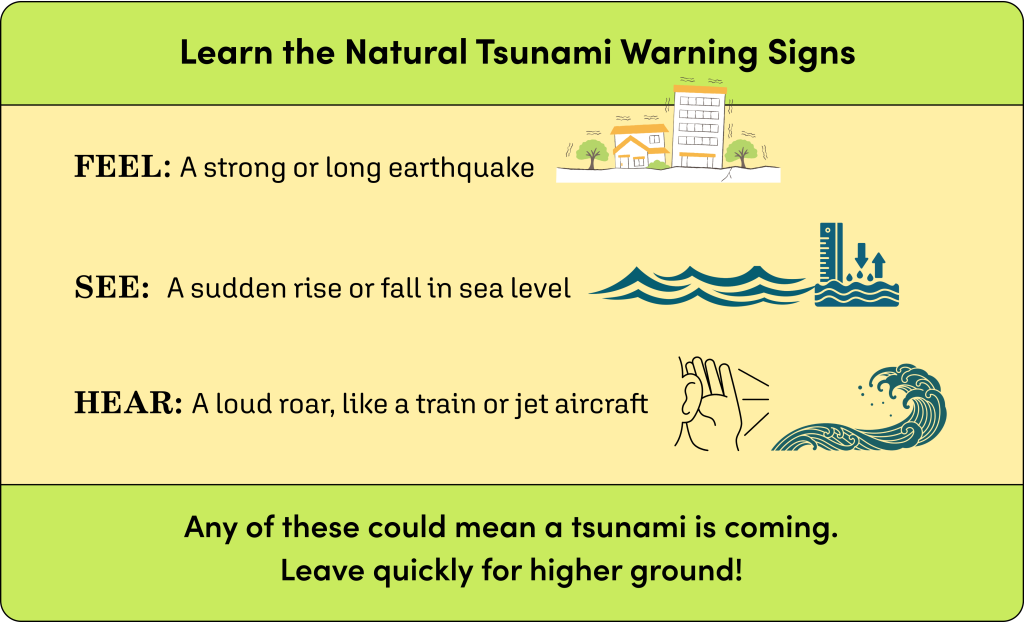

If you:

- Feel a strong or long earthquake

- See a sudden or extreme rise or fall in sea level

- Hear a loud roar from the ocean, like a train or airplane

These signs could mean that a tsunami is coming. Leave quickly and get to higher ground.

Tsunamis in Hawaiʻi

Tsunamis have always been a part of life in Hawaiʻi. Ancient Hawaiian chants describe large, destructive waves that killed coastal dwellers. Modern observations of tsunamis in Hawaiʻi date as far back as 1813.

Since 1900, tsunamis have claimed the lives of 263 people in Hawaii, more deadly than any other kind of natural disaster. In that time, there have been nine large distant tsunamis with wave heights over ten feet. Six significant local tsunamis have been generated by earthquakes, landslides and volcanic activity within the Hawaiian Islands.

In 1863, a local tsunami off the southeast coast of Hawaiʻi Island produced 17-foot waves that left 47 people dead in coastal villages.

In 1946, an 8.6-magnitude earthquake in Alaska produced a tsunami that killed 159 people on Hawaiʻi Island, Maui, Kauaʻi and Oʻahu – the deadliest tsunami in state history. Wave heights measured 54 feet in the Waikolu Valley on Molokaʻi.

In 1960, a 9.5-magnitude earthquake in Chile (the most powerful earthquake ever recorded) triggered a tsunami that killed 61 people in the Hilo area of Hawaiʻi Island. Wave heights in Hilo reached 35 feet.

In 1975, a local tsunami off the southeast coast of Hawaiʻi Island killed two people in Halape and produced waves 46 feet high.

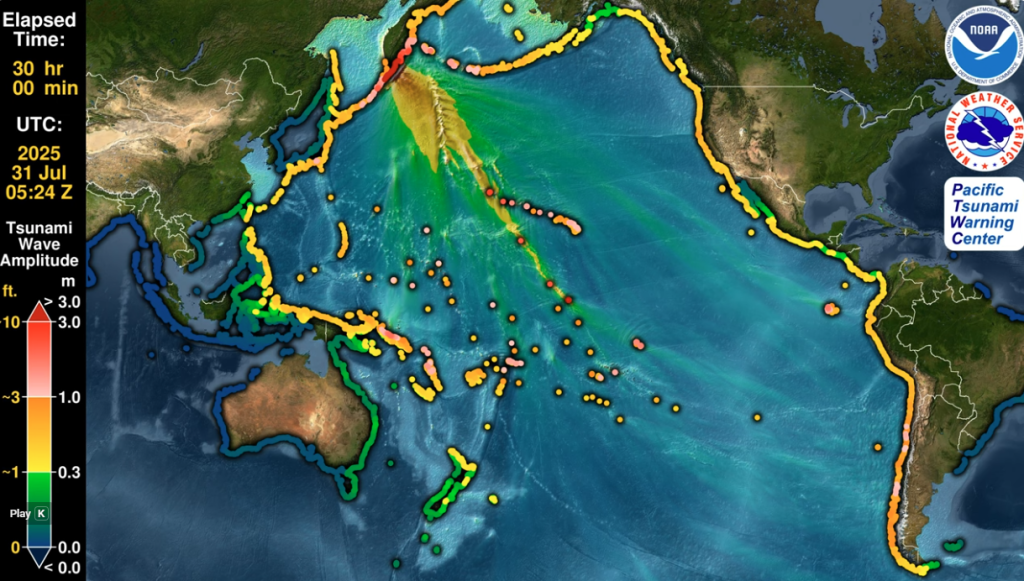

In the 21st century, massive earthquakes continue to produce threatening tsunamis in the Pacific region. In 2011, a 9.1-magnitude earthquake in Tohoku, Japan, killed 18,000 people there and produced damaging 12-foot waves in Hawaiʻi. In 2025, an 8.8-magnitude earthquake in Kamchatka, Russia, triggered tsunami evacuations in Hawaiʻi and produced wave heights of 5 feet in Hilo and Kahului.

Prepare for Tsunamis

Because tsunamis can happen anytime – day or night, in any season – it is important to prepare for tsunamis right now. There are three main aspects to tsunami preparedness: Information, supplies and plans.

Information is essential for tsunami preparedness. Complete the following tasks to be informed:

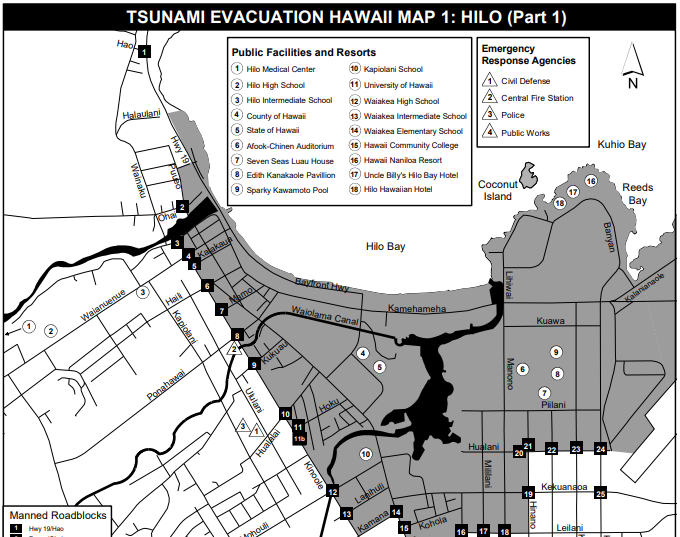

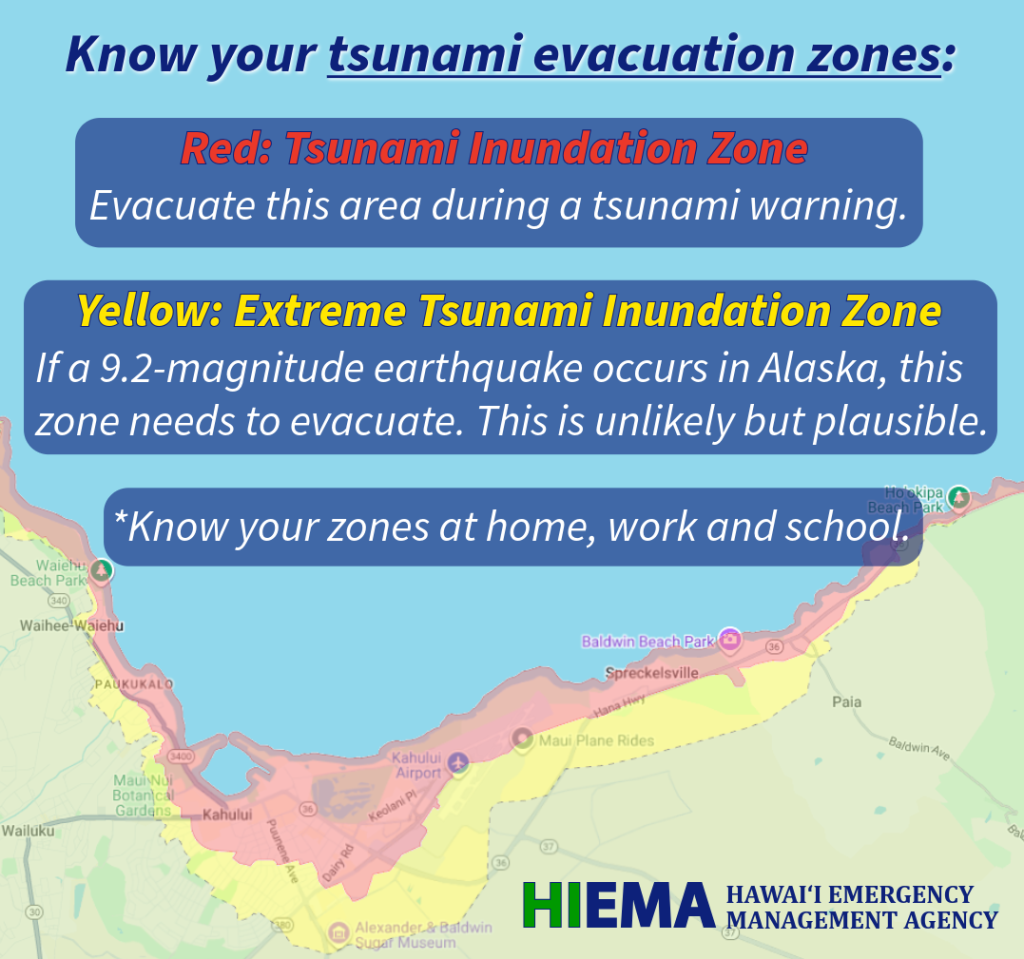

First, sign up for emergency alerts for the area you live in by going to ready.hawaii.gov/alerts. Your county’s emergency management agency will send immediate notifications to your cell phone when there is a tsunami or other threat. Second, find out if you live or work in a tsunami evacuation zone by using the Tsunami Aware app. Make sure you check the tsunami zones for your home, work and school.

Hawaiʻi has two types of tsunami zones. The red zones are tsunami inundation zones that must be evacuated during any tsunami warning. The yellow zones are extreme tsunami inundation zones. These areas would be evacuated during an extreme tsunami that could result from a 9.0-magnitude earthquake in Alaska. An extreme tsunami is unlikely but plausible based on studies by tsunami scientists.

It is important to note that schools have their own evacuation plans to get students to safety. If an evacuation is ordered when your child is at school, do not go to the school. Proceed with your own evacuation if you are in a tsunami evacuation zone. You can find out beforehand what your child’s school evacuation plan is by going to the school’s main office.

In order to evacuate quickly, you should have a Go Bag ready with emergency supplies that can sustain you away from home, including water, food, medicine, power and a communication source. Useful things to include in a Go Bag include a radio, a local map, a cell phone battery, cell phone charger, multi-tool, first-aid kit, high-energy snacks like protein bars or nuts, a portable water filter, a flashlight and an extra layer of clothing. You also need to pack supplies for your pets, including water, food and medication. Find a full list of suggested Go Bag items at FEMA’s Build a Kit page.

Finally, make sure your family knows your emergency plan. Know what roads lead from your home or work to high ground. Designate the home of a family member or friend that is away from the coast at a higher elevation. Also identify a safe place that you can reach on foot if vehicle traffic is too heavy. Have a hard copy of important phone numbers, including family members, work, school and doctor, in case your cell phone dies and you need to borrow a phone.

During an emergency, local communication networks can sometimes become overloaded, blocking communications. In this case, it is helpful to have a long-distance contact on the mainland or on another island who is outside of clogged local networks. This person can be a central communication point for your family. You can relay information to this contact, and they can relay information back to other local people.

Make sure your family members know how to send a text message. In an emergency, text messages are more likely to get through a clogged network than voice calls, because text messages use less bandwith.

For more information on emergency communication, visit FEMA’s Make a Plan page.

Responding to a Tsunami

A network of tsunami warning systems operates 24/7 across the United States and the Pacific region. In this system, when an earthquake occurs, scientists use seismological readings and deep-ocean data assessments to determine if a destructive tsunami could be generated. Scientists then use forecast modeling to predict when, where and how large tsunami waves may be. If it is forecast that there is a threat to people or property, warning messages are sent to the general population.

In Hawaiʻi, information warning systems that we can use include emergency alert systems on TV and radio, wireless emergency alerts for cell phones, and an outdoor siren system. If you hear an outdoor warning siren, it means an emergency is happening or may happen soon, and you need to check you cell phone, TV or radio for emergency instructions.

If you receive a tsunami evacuation order, or notice the natural warning signs of a tsunami, get to high ground as quickly as possible. If the tsunami is still distant, you can take your Go Bag and evacuate in your vehicle. If the tsunami is local, you may need to evacuate on foot right away. Get away from the coast and get away from inland waterways. Find high ground or move past street signs that say “Leaving Tsunami Zone.” Always follow instructions from emergency personnel.

You can also vertically evacuate in urban areas. Go to a sturdy building made of reinforced concrete or structural steel that is ten stories or taller. Get to the fourth floor or above.

If you are in a safe place and don’t need to evacuate during a tsunami, stay in that safe place and do not travel. People who evacuate unnecessarily add to traffic on the roads, making it harder for people who do need to evacuate, and making it harder for emergency vehicles to operate and help people.

Boating Safety in a Tsunami

Firstly, all boats should be equipped with emergency supplies on board, including water, food, first-aid, fuel, tools and communication devices. Make sure you have a VHF radio or a NOAA Weather Radio to receive tsunami alerts and official emergency instructions.

Boats in harbor are more likely to suffer tsunami damage than boats in deep water. If you have time, move your boat to deep water of 100 meters or deeper. However, if you do not have time to move your boat before the forecasted wave impact, leave your boat in harbor and get yourself to high ground where you will be safe.

If you are out to sea during a tsunami, do not attempt to return to port until instructed to do so by marine authorities. Ports often suffer debris damage from tsunamis and become unnavigable. In addition, dangerous currents and unusual ocean movement can remain for hours or days after a tsunami.

For more information on tsunami boating safety and recommended supplies, consult the Hawaiʻi Boater’s Hurricane and Tsunami Manual, published by the University of Hawaiʻi Sea Grant College.

After a Tsunami

It is important to wait for an official all-clear before returning to your home or traveling after a tsunami. Remember that tsunamis are series of waves that can continue for several hours. Do not enter the ocean until Ocean Safety has reopened beaches; dangerous currents can remain for days after a tsunami. Be extremely cautious around lingering floodwaters where dangerous debris may be hard to see. Infrastructure stabilization and official emergency operations may require hours or days before an evacuation is safe to return to.